This document will be shared alongside a collective learning workshop. Pictures to follow!

“It is only the oppressed who, by

freeing themselves, can free their oppressors”

-Pedagogy

of the oppressed. Paulo Freire

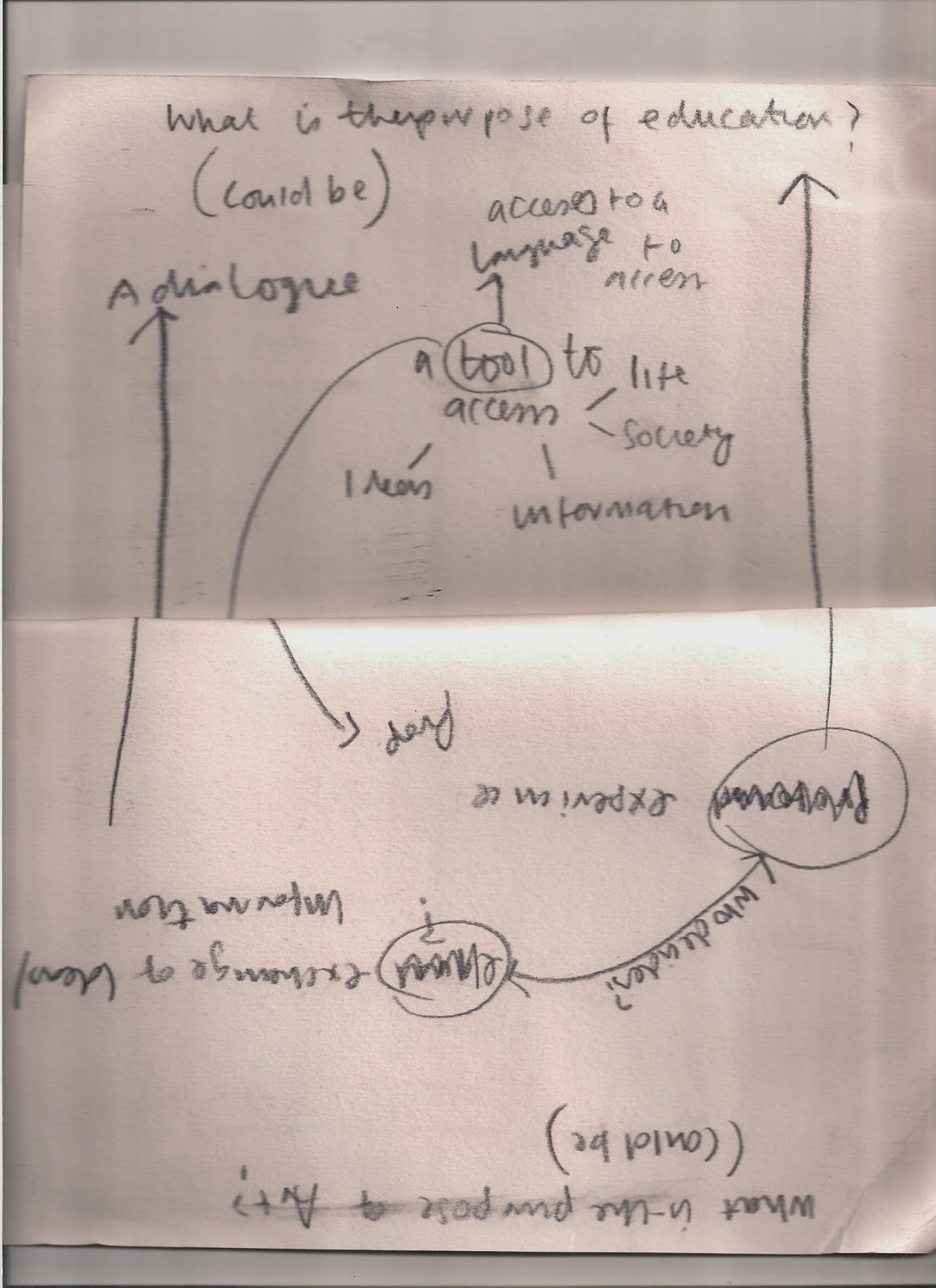

In considering what

art, education, and furthermore art education, might be for or how ‘arte util’

(a Spanish phrase meaning ‘useful art’ perhaps first coined as long ago as 1969

by Eduardo Costa and more recently by Tania Bruguera, amongst others) might be

made it seemed necessary to explore and account for our own discreet

professional lives. Importantly, we sought to preface any decision-making about

outcome with an investigation into the wealth of activity, including the

sometimes routine or humdrum, of our day-to-day lives and the research we were

carrying out as part of the Critical Pedagogy module. Therefore, the material

that we’ve collected ranges from the mundane to the revelatory, from email

trails, overheard conversations and planning input to notes from seminars,

lectures and recommended reading.

It seemed appropriate

to retain and bind it all, unedited, as an honest document to unpick, discuss

and arrive at an almost inferential understanding of what we do in order to

draw some conclusions about what we might do as (socially engaged)

practitioners in the future.

It was through open discussion between

three different practitioners that we drew the conclusion that it was in the

space between nothing and something that the practice of critical pedagogy

could take place. This flexible space allows for risk taking and

misunderstanding to take place and an honesty about intentions to exist. It was through this honesty that democratised power

relationships and opportunities for genuine collective learning experiences

could be explored. Through

this collection of information and everyday actions we see the space between

nothing and something as an attempt to act against the mechinic thinking of the

institution and the pre-established orders where it could be argued that ones

experience has already been decided. This is especially prevalent in an

educational institution where the dialogue between the institution and the

people with in it has become an irrelevant nuisance, as suggested by Freire in

Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 1968. Instead it is an attempt to engage in a

meaningful conversation.

During the

conversation entitled ‘What Does Community Mean?’ in Gallery as Community: Art, Education, Politics, page 39,

Frances Williams, Head of Education at The South London Gallery, explains:

“The Gallery has given

me an amazing privilege to de able to have the kind of relationships that I wouldn’t

have been able to have had on my own, or if I was an individual artist rocking

up to the estate. And also, the gallery has been able to provide something for

the estate that they wouldn’t have had if we weren’t there.

There have been points

where I think I can sit in quite a critical position in relation to the rest of

the gallery. The estate itself has its own internal differences about what

people think we’re there to do, which I try to respect.

But all of that has

been a conversation the wouldn’t have taken place without being part of an

institution.”

From this we start to

see forming a complex, co-dependant, conflicting relationship between the

established and accepted institution and a space within it that acts as the

point of public engagement. This public space, where an honest and democratised

approach is taken towards the power relationships present, begins to act as a

wedge, a point of conflict, a space where Ranciere’s idea of dissensus can take

place within an institutional context, a space to offer alternative ways to

interacting.

In this instance we

suggest not a physical space as such but the creation of a metaphysical space

through the action of a collective learning experience.

"Really, all you need to become a

good knitter are wool, needles and hands…”

Elizabeth

Zimmermann.

British-born

knitter known for revolutionising the modern practice of knitting.